Headlines matter: Topline takeaways from a recent ultra-processed food study are wrong and irresponsible

A study that considered pizza and cake "plant-based foods" tells us little about plant-based meat and heart health. But that didn't stop a flurry of misleading headlines.

You may have noticed a wave of recent headlines making some pretty bold and scary claims about plant-based meat products.

But is that really what a recent study on ultra-processed foods (UPFs) published in The Lancet found? No. Not remotely.

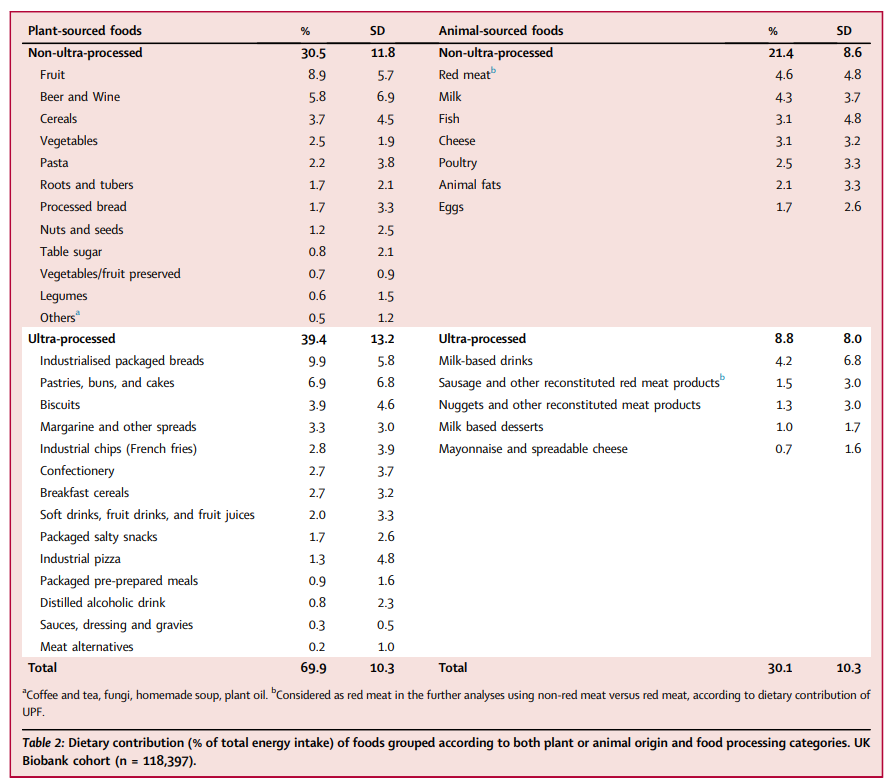

In reality, participants in the study in question barely ate any plant-based meat at all. Plant-based products designed as alternatives to animal-based meats like burgers and sausages represented only 0.2 percent of the cohort’s intake, far less than 1/100th of what they consumed, and a lot of the “plant-sourced foods” contained animal-sourced meat, eggs, and dairy.

Yet multiple headlines made it seem like plant-based meat was the focus of the study. This is a big problem, as most people don’t read the underlying scientific papers of every headline they see. If such stories are published in familiar, trusted outlets, many people likely take these headlines at face value. Having recently compiled a 62-page report synthesizing the available evidence of plant-based meat and health, it was clear to me that something was amiss.

I worked for several years in medical communications, where patient education and open science advocacy were two of my main areas of focus. Leaving health to enter the food space, the shockingly poor quality of evidence and reporting on nutrition topics is a source of major concern for me. It is not reasonable to expect consumers to read every scientific paper themselves, and because everyone has to eat, we rely on scientific journals and journalists to take the abundance of research (both good and bad), find the signals in the noise, and communicate data and evidence simply and accurately.

This paper is not unique, but it is a particularly egregious example of faulty research being accepted in a well-known journal and then distorted in its reporting. So, in this article, I’ll dive into the study and unpack what the research underlying these headlines actually said.

So what was the study about, and what were the participants really eating?

The study was “observational,” meaning it looked at data gathered from people going about their daily lives, and followed them over time to look for patterns in health outcomes. The food data used was based on information from 24-hour food diaries taken from participants at least twice between 2009 and 2012 (which, it should be noted, is before any of today’s next-gen alternative protein products were even developed). The foods eaten were categorized by researchers and grouped into “plant-sourced” and “animal-sourced foods,” and these groups were sub-divided into ultra-processed, and not ultra-processed. Using the health data collected from study participants in the years following their completion of the food diary, researchers looked if there were any patterns in outcomes associated with people who ate these different groups of foods.

If you’re thinking “this doesn’t sound like a study designed to look at the health impacts of plant-based meat,” you’d be absolutely right.

The definition of “plant-sourced” used in the study is also not one that anybody would actually use in day-to-day life. For starters, a large proportion of foods in this category used in the study contain animal-based meat, eggs, and dairy, they just do not list animal products as the main ingredient. For example, a ready-made “meat feast” pizza with conventional meat and cheese, under the definitions used by this study, would be categorized as a “UPF plant-sourced food” (yes seriously).

The three food groups comprising the largest share of the ‘plant-sourced’ category were bread (9.9%), pastries and cakes (6.9%), and biscuits aka cookies (3.9%), but the category also included alcoholic spirits, energy drinks, pizza, sweets, and salty snacks. “Meat alternatives” was the smallest single category in the ‘plant-sourced UPF’ group, and according to the study’s supplementary materials, tofu, textured vegetable protein, and tempeh were included in this category alongside plant-based meats designed to mimic the experience of animal-based meats, such as burgers and sausages.

Using this problematic definition and faulty study design, researchers found that high consumption of “plant-sourced” UPF (and the combined UPF group) was correlated with increased health risks. High consumption of packaged sweets, pizza, and pastries may lead to poor health outcomes? Hardly groundbreaking findings.

Shortly after the study and its corresponding press release were published, several nutrition and dietetics experts working with the Science Media Centre expressed concern over its methodology and conclusions and shared expert summaries of the findings with journalists.

“This is an interesting paper – unfortunately people could possibly assume from the press release that the association with cardiovascular disease risk is specific to meat and dairy replacement plant-based foods such as plant-based sausages, nuggets and burgers. This is not what the paper shows.” Dr Duane Mellor, Dietitian and Spokesperson for British Dietetic Association commented.

Unfortunately, this didn’t stop numerous media outlets from running with headlines that maligned plant-based meat based on a study that barely even looked at plant-based meat products.

What do we know about plant-based meats and nutrition?

It’s important to continue research into the health impacts of plant-based alternatives to conventional animal foods. Such research is especially important for plant-based food innovators as they work to optimize the nutritional value of products.

But to get an accurate picture of the health outcomes associated with eating plant-based meat — especially when these foods are eaten in lieu of conventional meat products — studies need to look at those products specifically.

Thus far, the studies that have looked at plant-based meat specifically using randomized controlled trials (rather than observational studies which are less able to shed light on the causality), report findings very different from the recent Lancet paper.

A systematic review from early 2024 looking at randomized controlled trials found several positive health effects associated with swapping plant-based in for conventional meat.

These trials (generally, although there was some variation in study design) took two similar groups of people and gave one group plant-based meat and the other group an equivalent portion of conventional meat, keeping other things the same, and compared the differences both from the start to the end of the study, and between the two groups.

Similar findings were reported in a paper published in the Canadian Journal of Cardiology in June 2024, which reviewed studies published from 1970 to 2023 and found that “risk factors for heart disease, including total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol and body weight, improved when various animal-based meats were replaced with a substitute made from plants.”

So what did we learn from all of this?

The paper behind these headlines contained no evidence that plant-based meat was associated with elevated heart risks, and if we look at randomized controlled trials looking specifically at plant-based meat (rather than studies looking at plant-based meat as a tiny subset of foods it has very little in common with and extrapolating), research suggests that swapping plant-based meat for conventional animal-based meat (particularly processed meat) could actually offer health benefits. As always, more research is needed to further explore these findings.

While no meaningful conclusions can be drawn from the latest Lancet paper about the healthfulness of plant-based meat products, this scenario underlines the very real importance of quality, accurate, evidence-based reporting on nutritional science to help people make informed choices about the food they eat, including simple swaps that could benefit their health. In the world of nutrition, people have limited bandwidth to devote to improving their diets, and so there is a huge opportunity cost to misleading reporting that unnecessarily demonizes foods that could actually be an easy, healthful swap for many people.

For more on the nutritional properties of plant-based meat, check out this report from GFI Europe on plant-based meat and health.